|

Landing Craft Tank (Mark 3) 318 - LCT (3) 318.

An Amazing WW2

Landing Craft Survivor that Served

the UK into the 1970s!

Background Background

His Majesty's Mk3 LCT 318 was built by Teesside Bridge and Engineering Company and

launched on February 14th, 1942. She was 192 feet in length and 33

feet across her beam and could carry 5 tanks or 350 tons of mixed cargo. Her

armament comprised two 20mm Oerlikon guns and her crew complement, including her

commanding officer and his second in command, was a total

of 12 men. This is the story of one Landing Craft Tank seen through the eyes of the

craft's electrician.

[Photo; A Mark 3 LCT beached with ramp down.

© IWM (A 10064)].

Living Conditions

This

class of vessel was designed for frequent but short duration

journeys across the English Channel or similar

stretches of water, so living

accommodation was not a major consideration in its design.

However, in practice, we lived under quite dreadful

conditions for years, especially when operating in hot

climates, which we sometimes did in the Mediterranean

when there were few modifications to alleviate our misery.

Later Mk3 'Star' LCTs sent out to the Far East

were more suited for purpose and far better equipped. These LCTs bore pennant

numbers in the 7000 series and had a crew

complement of nineteen men.

The crew accommodation was

at the after end with the officer's

accommodation at deck level. The officers' very small cabin

contained two bunks. They used the wheelhouse as a day cabin by stripping out

the wheel and they shared one very small toilet. The crew’s quarters, some 19ft

by 18ft, were below deck right aft, which contained

the capstan motor and control gear, 10 crew lockers, 2 small tables, 1 small

paraffin heater, 10 kit bags and 10 hammocks. The crew’s toilet facilities were

at the forward end of the craft The crew accommodation was

at the after end with the officer's

accommodation at deck level. The officers' very small cabin

contained two bunks. They used the wheelhouse as a day cabin by stripping out

the wheel and they shared one very small toilet. The crew’s quarters, some 19ft

by 18ft, were below deck right aft, which contained

the capstan motor and control gear, 10 crew lockers, 2 small tables, 1 small

paraffin heater, 10 kit bags and 10 hammocks. The crew’s toilet facilities were

at the forward end of the craft

[Photo;

the author Jim Routledge].

The grossly overcrowded

living space caused excessive

condensation which, at night,

required hammocks to be covered with waterproofs

to prevent the blankets becoming soaked. Not surprisingly

these unhealthy conditions caused or exacerbated chest

ailments and tuberculosis, which

were rife amongst LCT crews.

The galley was adjacent to the officers'

quarters with its coal-fired cast iron

stove, that an imaginative person might liken to a

very crude Aga. Hot water came

from a 4 gallon tank attached to the stove,

which was intended to cater for the crew's needs. The

nearby coal bunker served as a top on

which

all the meals were prepared. There was no official cook amongst landing craft

crews, so the author assumed the role without any training.

He continues with the story of LCT 318.

Early Days

318 was commissioned during March/April 1942 and was

assigned to the 4th LCT Flotilla under her commanding officer, Lt

Green. She was thought to have been involved in the infamous

Dieppe Raid in August 1942 but

details were sketchy and not worth recording here.

Our crew joined LCT 318 in

March, 1943, while she was docked at

Southampton. She was part of the 11th

LCT Flotilla. We were transferred from Scapa Flow, where we had been providing

protection for capital ships. The protection involved rigging steel anti-torpedo

nets on to Mk3 LCTs, which were then moored alongside the larger vessels. The

nets were then lowered into the water to give protection to our ‘Big Sisters.’

In providing the ring of steel for the larger ships, it seemed landing craft and their crews

were regarded as expendable by the top brass!

The Mediterranean The Mediterranean

In April, 1943, LCT 318 and her sister ships of the 11th Flotilla

sailed with another flotilla to Gibraltar. The journey took ten days and was not

without incident. The flotilla navigator executed a 90 degree turn at midnight

on a moonless night, no doubt as

part of an anti submarine strategy, but one LCT did not see the signal.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

In a three column

formation, a collision during such a manoeuvre was almost

inevitable but, fortunately, the sloping bows

of the two craft involved, allowed one to ride up the side of the other and, after some delay,

the two craft disengaged and we continued in convoy. We

arrived safely in Gibraltar, our arrival being duly reported by the Germans and

by the Daily Mirror, much to the relief of my parents.

In

the following weeks, we collected a variety of cargoes from

numerous ports on the North African coast, as we made ready for

Operation Husky -

the landings in Sicily. We also made trips to Malta, often courting the attention

of German and Italian fighter planes. Many landing craft suffered fatalities

from air and submarine attacks. In

the following weeks, we collected a variety of cargoes from

numerous ports on the North African coast, as we made ready for

Operation Husky -

the landings in Sicily. We also made trips to Malta, often courting the attention

of German and Italian fighter planes. Many landing craft suffered fatalities

from air and submarine attacks.

In July 1943,

LCT 318 and her sister ships loaded at Benghazi. We

embarked men of the 99th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment and set sail for Malta,

where the invasion fleet had assembled. The onward journey to Sicily was

memorable for a dreadfully sad spectacle,

which we witnessed as we

approached Sicilian waters.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

We were not involved

in the initial assault, so we had a

grandstand view of the unfolding events from a relatively

safe distance. We witnessed Allied gliders

crashing into the sea, after inexperienced American pilots released them too early

when they came under enemy

gunfire, which probably included some from our own guns! I also

recall a hospital ship being attacked, even though she was well away from the

invasion fleet and fully illuminated.

When 318 eventually beached, she discharged her troops at Avola

(Green Beach). The men landed dry-footed and met little opposition. We then

ferried POWs to captivity, including some Italian troops

wearing their pajamas. They all had the presence of mind to pack their bags!

We then engaged in ferrying munitions and supplies from

cargo vessels to the shore as we followed the Allied

advance northwards along the coast of

Sicily.

On the 3rd of September, 1943,

we embarked lorries and miscellaneous war materials at

Messina and ferried them to the beach at Reggio de Calabria. The army

had shelled the area around the landing beaches from across the Straits of Mesina

with the Air Force in support.

Enemy resistance on landing was, consequently, fairly light

as the Allies harassed the retreating Germans. One such example was at Vibo

Valentia where the landing started quietly but, when a German Armoured division arrived

on the scene, it caused quite a bit of trouble.

[Photo;

right to left: 320, 318, 413 and 399 on Porth Mellon beach, St

Marys, Isles of Scilly after the gruelling

trip from Gibraltar].

In October of 1943,

when in Taranto, we were recalled to our base in

North Africa. On arrival there, the backlog of repairs requested over several

months were finally completed, after which we took passage to

Algiers with our base staff, where we stayed for several days. Such was the secrecy

about our next assignment that speculation was rife, the most likely outcomes

being home or the Far

East. Fortunately for us we were homeward bound.

Return

to England Return

to England

In November 1943, we arrived in Gibraltar where

we replenished our stores and

spent our accumulated pay on luxuries that were not available back home. We set sail for England on the 3rd or 4th

of November and proceeded westwards into the Atlantic to avoid submarines in the

Bay of Biscay. The first five days were calm but, for reasons unknown, we

proceeded at a very slow pace. On the sixth day, we encountered Force 9 gales and

our convoy of twenty four craft were scattered.

[LCT

354 on Newford Rocks].

318 found herself alone and without radio

contact, owing to storm damage. The seas were mountainous with waves of 30 feet

or more and substantial damage was caused. The fuel pumps on both main engines

ceased to function and we had to resort to hand pumping fuel to the engines

using the semi-rotary pump, which was normally used to prime the engines. This

arrangement continued for the remainder of the five days and nights it took us

to arrive back in England.

We had no radio, no modern day navigation aids and no opportunity to

take sun or star readings because of the cloudy weather. Throughout that

period the 318 was totally lost! We headed in the general direction of

where we thought England should be. The gale continued to blow and our

concerns grew as the stove began to disintegrate, making it increasingly

difficult to make hot meals

and drinks. We had no radio, no modern day navigation aids and no opportunity to

take sun or star readings because of the cloudy weather. Throughout that

period the 318 was totally lost! We headed in the general direction of

where we thought England should be. The gale continued to blow and our

concerns grew as the stove began to disintegrate, making it increasingly

difficult to make hot meals

and drinks.

[Photo; a commendation from The Lords

Commissioners of the Admiralty].

On or about the ninth day out

from Gibraltar, a Sunderland flying boat on anti-submarine duty discovered us

and set us on a course for England. At dusk, on the

tenth day, still struggling through the storm, land was sighted. A suitable beach

was identified and, in near dark, we ran

up the beach at full speed. The crew of 318 collapsed from

exhaustion and the next morning we discovered we had landed on St Marys, one of the Isles of Scilly. We were later joined by another four craft,

which had been escorted in by the naval unit based on the Islands.

We remained there for about two weeks, being

pumped out and undertaking emergency repairs. When the high spring tides came,

we re-floated and made our way to Swansea for repairs. The ship manager later

reported that rivets ‘by the bucket full’ had been recovered from the

double bottom and that if we had been a welded craft we would not have survived.

Let me here give thanks to the builders at Teesside who did such a marvelous job

in the construction of 318 which likely saved our lives. Sadly, two of the craft that

sailed into that storm did not survive the journey.

Training for D-Day Training for D-Day

We departed Swansea in February 1944, via Cardiff, to have the

compass swung and the degaussing tested, arriving in our home port

of Southampton, where we were joined by our sister ships of the 11th

LCT Flotilla. They had all been undergoing repairs at different yards, mainly in

the Liverpool area.

A period of flotilla training or ‘working-up’ followed, after which we

returned to Portsmouth, where we were to have Mulock extensions fitted to our

ramp. We later discovered this was to accommodate a new ‘secret

weapon’…the Duplex Drive Sherman tank or ‘swimming tank’ as they would become

known. These

tanks had been fitted with a waterproof canvas skirt, which allowed them to

disembark at sea and then ‘swim’ for the beach.

Manning the Sherman DD tanks were the men of

the Canadian Fort Garry Horse. On D-Day, the DD tanks were intended to be launched two miles off the

beach, thereafter, they would make their own way to the beach, lower their

canvas skirts and then engage the defenders. Such a sight would likely have a demoralising effect

on the enemy, whilst providing significant back-up for the

incoming assault infantry.

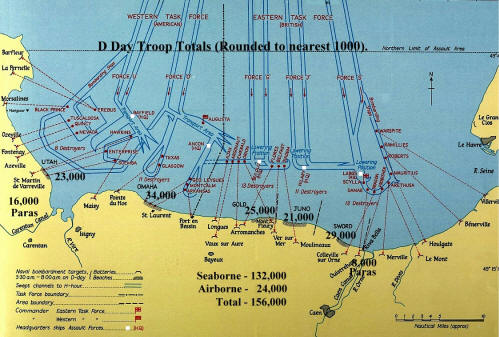

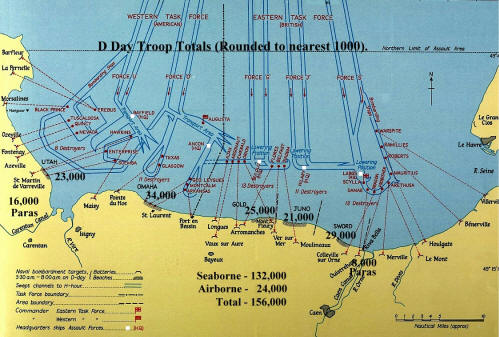

D-Day

Much has already been written about the

uncomfortable journey across to Normandy on June 5th/6th.

Suffice to say here that the seas were rough at Bernieres

sur Mer on Juno beach but the men of the Fort Garry Horse were landed dry

footed. LCT 318 ran directly onto the beach to discharge her tanks

but there were problems. Enemy gun and mortar fire was quite heavy as we made our final dash

and just short of the beach, the stern of the craft forward of us swung round

and collided with our bow, causing damage. With a solidly jammed bow door, none

of our 30 ton tanks could disembark but when the front-most tank pushed against

it, it gave

way under the extreme pressure. Much has already been written about the

uncomfortable journey across to Normandy on June 5th/6th.

Suffice to say here that the seas were rough at Bernieres

sur Mer on Juno beach but the men of the Fort Garry Horse were landed dry

footed. LCT 318 ran directly onto the beach to discharge her tanks

but there were problems. Enemy gun and mortar fire was quite heavy as we made our final dash

and just short of the beach, the stern of the craft forward of us swung round

and collided with our bow, causing damage. With a solidly jammed bow door, none

of our 30 ton tanks could disembark but when the front-most tank pushed against

it, it gave

way under the extreme pressure.

[Extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' showing disposition

of LCT 318 just prior to D-Day.Click to enlarge].

Despite the heavy

enemy response to our arrival, we avoided major damage but two craft from our flotilla were lost and

they took casualties, notably two men killed aboard our

sister ship LCT 317. We withdrew from Juno beach to a safe distance, while on

call for other tasks if required. We spent the remainder of the day cruising

offshore, while the beach-head was secured. For several days following,

we ferried a variety of cargoes back and forth

between England and France.

On one such trip back to Normandy, 318 embarked

American troops for Omaha beach.

On the journey, the weather worsened and we were soon in the grip of a full

blown gale. We anchored off the beach, hoping

to ride the

storm out but we lost both Kedge anchors and both engine sand traps became

clogged, resulting in the loss of both engines due to the lack of coolant. We drifted against the

floating roadway connecting the Mulberry Harbour

to the shore and regretfully sank many of their supporting barges. The 318 was

at the mercy of the sea and was finally washed up on to the beach…..we were helpless to prevent

it. On one such trip back to Normandy, 318 embarked

American troops for Omaha beach.

On the journey, the weather worsened and we were soon in the grip of a full

blown gale. We anchored off the beach, hoping

to ride the

storm out but we lost both Kedge anchors and both engine sand traps became

clogged, resulting in the loss of both engines due to the lack of coolant. We drifted against the

floating roadway connecting the Mulberry Harbour

to the shore and regretfully sank many of their supporting barges. The 318 was

at the mercy of the sea and was finally washed up on to the beach…..we were helpless to prevent

it.

[Photo;

DD tanks during exercises

in the UK prior to D Day. With the canvas screen raised and engines

running, they were ready for the ramp to be lowered.

© IWM (H 35179)].

There were hundreds of landing craft lost or

damaged during the great storm that raged for three days beginning the third

week of June. We lay helpless on the beach for a week or 10 days until essential

repairs were carried out by a beach party to make her seaworthy. In that

period, we had repaired the engines and were able to limp back home to Southampton. The planners

had anticipated far greater losses amongst the landing craft during the Normandy

landings, so crippled or damaged craft

like LCT 318 were dispensable. She was laid up and we, her crew, were

paid off.

Epilogue

My association with His Majesty’s Landing Craft Tank 318

had come to an end. I spent the remainder of the war in the UK,

which included a very cushy

number in Poole Harbour looking after American Lend-Lease craft awaiting

repatriation after the war.

318 was subsequently converted to an Engineering Repair Craft

designated LCT(E) 318 and beyond that to Maintenance and Repair Craft 1097. I suspect she was intended

for duties in the Far East but have failed to discover if she arrived there. One of her sister craft LCT 320, also built at Teesside and

assigned to the 11th Flotilla on D-Day, became Naval Servicing Craft

1110 attached to the submarine depot ship Medway supporting the 10th

Submarine Flotilla out of Singapore. 318 was subsequently converted to an Engineering Repair Craft

designated LCT(E) 318 and beyond that to Maintenance and Repair Craft 1097. I suspect she was intended

for duties in the Far East but have failed to discover if she arrived there. One of her sister craft LCT 320, also built at Teesside and

assigned to the 11th Flotilla on D-Day, became Naval Servicing Craft

1110 attached to the submarine depot ship Medway supporting the 10th

Submarine Flotilla out of Singapore.

[Photo; This 1970 stern shot of MRC

1097 taken in Bahrain was provided by Mr. Richard Gleed-Owen].

On the subject of what happened to LCT 318, John Rowsell provides the

following information. My understanding is that LCT 318 was refitted to serve

as a Maintenance and Repair Craft (MRC1097) - as James explains in his story. I

know that in the early 1950s she was based in Malta, was in the Suez operation

in 1956, and turned up in Bahrain in 1962 as base ship for the 9thMSS/MCMS from

1963 (I think) to 1971. I served on board her for 2 years in 1966/67 as a Tiffy.

Little did I know then what her story was. I believe she was sold out of the RN

in 1971.

LCT 318 was an extremely lucky craft. We only ever sustained three

casualties, none was fatal and

only one was due to enemy fire. If the stoker in question had remained at his

station in the engine room,

he would not have been hit by a piece of flying shrapnel, which severely injured

his nose. However, it should be remembered that many similar craft, and the men

who served aboard them, did not survive the war. Thank you for reading my

personal recollections. By doing so, you have helped preserve the memory of those

who served their country at a time of great peril.

Further Reading

On this website there are around 50

accounts of landing craft

training and operations and

landing craft training establishments.

There are around 300 books listed on our 'Combined Operations Books' page which

can be purchased on-line from the Advanced Book Exchange (ABE) whose

search banner checks the shelves of thousands of book shops

world-wide. Type in or copy and paste the title of your choice or

use the 'keyword' box for book suggestions. There's no obligation to

buy, no registration and no passwords. Click

'Books' for more

information.

Acknowledgments

This

account of the Mk3 LCT 318 is by Wireman (Electrician) James B Routledge D/MX 95943.

Unless otherwise credited, the photos were also provided by him.

Transcribed by Archivist/Historian Tony Chapman of the LST and

Landing Craft

Association (Royal Navy) from information provided by James and further edited by Geoff Slee for website

presentation, which included the addition of maps and

photographs. Landing Craft

Association (Royal Navy) from information provided by James and further edited by Geoff Slee for website

presentation, which included the addition of maps and

photographs.

|